What do monsters have to do with queer books? From Frankenstein’s monster to Nosferatu to the most obscure of X-Files cryptids, monsters are threats to “normal” straight society. There’s definitely rich analysis to be had about the historical associations between queerness and monstrosity. But monster media is also so much fun. Any Jennifer’s Body devotee knows that some of the best queer media plays up the thin line between fear and desire. Who doesn’t want the adrenaline rush of thinking they’re going to be eaten by Megan Fox?

While Frankenstein might be the first book we think of as the “monster novel,” its queer descendants are taking up the inhuman body to explore queer sexualities and life. If you’re chasing the thrill of reading authors like Carmen Maria Machado, Gretchen Felker-Martin, or Shirley Jackson, put Monstrilio at the top of your reading list.

When eleven-year-old Santiago passes away, his mother doesn’t cry. Instead, Magos does what feels natural: she cuts open Santiago’s body and extracts a piece of his lung, storing it in a jar for safekeeping. The lung becomes her secret stowaway, accompanying Magos to her mother’s home in Mexico City, where she retreats to grieve. On little but a folktale and a hunch, Magos spoons some chicken broth into the jar, watching for signs of life. Remarkably, the tiny piece of tissue grows and grows into a little creature, affectionately named Monstrilio. But the more the “grief creature” grows, the more his family struggles to satisfy his hunger.

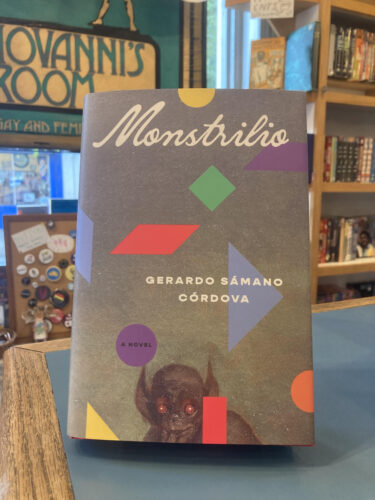

Monstrilio is Gerardo Sámano Córdova’s debut novel. Divided into four parts, the story dedicates a section to each of its four central characters: Magos, Lena (the woman who is in love with her), Joseph (Santiago’s father), and a mysterious “M.” A writer and artist from Mexico City, Córdova’s affection for gothic images shines through his work. In Monstrilio, a family’s love for such a terrifying monster mirrors their struggle to reckon with their own queerness and deviance–the monster uncovers the monstrous within.

Grief might be where Monstrilio begins, but the story isn’t exactly a tear-jerker. Córdova’s writing is detached–the novel is ruled by an otherworldly logic from Magos’ very first cut into her son’s body. It’s the kind of dreamlike state when a loss is just so overwhelming that the pain becomes ambient, and nothing feels real. For Magos, if Santiago can be dead, maybe none of the rules of the world make sense. These logical slips give way to intimate, weighty realizations about grief that Córdova sneaks in between the more action-packed moments of the novel. The beats are quieter, but they’re certainly there. If you’re interested in reading about grief, Monstrilio offers a beautiful, human portrayal of how far a person will go to avoid confronting such an immense loss.

But as the moves forward, it becomes clear that Monstrilio is also built for fans of horror. Monstrilio’s uncontrolled hunger is made way more terrifying by his pointed fangs, jaw that can unhinge to the width of his body, and extra long limb built for swinging from branch to branch while he hunts. His family desperately tries to figure out how to contain him as he feasts on basement rats, neighborhood pets, and threatens to graduate to larger beasts. Córdova’s horror winks at genre conventions, but the way he writes gore is so visceral and inventive that it doesn’t land as redundant.

By the final section, Monstrilio has matured into a teenager, and his family encourages him to pass as human. He’s going to restaurants, working in a bookstore, and venturing onto dating apps to meet boys. As Córdova adopts M’s perspective, we realize that M doesn’t just feed on pets because he misses a meal, M is always hungry. Witnessing M’s desire to eat is so satisfying after reading three characters who repress their feelings so forcefully. Who can blame M? He wants to eat men! He was born this way, baby!

There’s an obvious parallel between M’s desire for men and his desire for human flesh. Córdova flirts with a commentary on social deviance that will resonate with queer readers, but it’s not overbearing. Rather than divorcing M’s queerness from his monstrous hunger, Córdova takes the likeness further, taking us through M’s teenaged dating app escapades as he tries to find – a boyfriend? A victim? The clever tension between cruising and hunting makes for a kinky, terrifying, and thrilling fourth act. It’s also what might align Monstrilio not with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but with Susan Stryker’s. Córdova doesn’t reinvest in “human” as a category any more than he invests in the straight or cis. In this book, the monster speaks back, and he doesn’t want to assimilate. — Leo